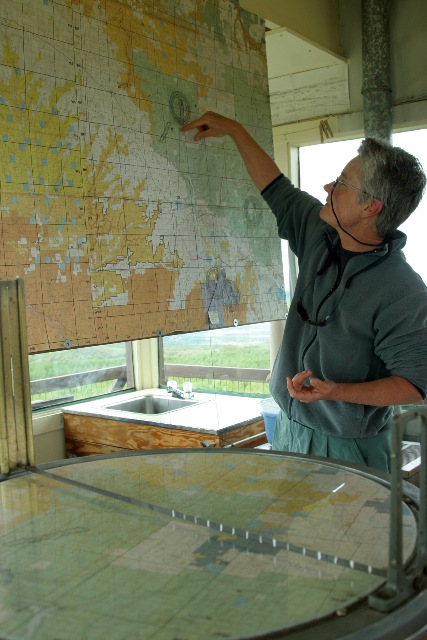

Benchmark Lookout's primary fire spotter, Barb Zinn, demonstrates the tower's map disk during a tour last Tuesday with the Dolores District's acting fire management officer, Dale Donohue. |

Barb Zinn, primary lookout at Benchmark fire tower, shows how she can pinpoint locations of fires on a drop-down map last Tuesday. |

Sondra Kellogg, director of the Colorado chapter of the National Historic Lookout Register, presents a certificate and plaque to be fixed to Benchmark Lookout ot Dolores District Ranger Steve Beverlin on Tuesday at the Dolores Public Lands Office. Benchmark's primary lookout, Barb Zinn, is at right. |

Barb Zinn waters her garden last Tuesday after a tour of Benchmark Lookout. |

|

BENCHMARK LOOKOUT - Four stories above a hilltop at the end of a four-wheel drive track in the Glade sits a glass box. It measures 14.5 feet by 14.5 feet and contains a bed, a sink and a refrigerator - both powered by the sun - books, maps and hand-drawn sketches of the views out each window, radio, cell phone and charger, map disk. Barb Zinn is the primary lookout at Benchmark, now in her seventh year at the tower. Though she is the primary lookout, she's not alone. A dedicated group of volunteers help Zinn staff the tower to keep watch over the landscape and the firefighters called to manage wildfires. Benchmark Lookout was built in 1970 to replace the older tower on Glade Mountain, originally built in 1941 by the Forest Service, Zinn said last week during a tour to the tower with acting Dolores District Fire Management Officer Dale Donohue, Sondra Kellogg with the Forest Fire Lookout Association and lookout for Mesa Verde National Park's Park Point Lookout, Dani Long. Kellogg was in Southwest Colorado to dedicate both Benchmark and Park Point to the National Historic Fire Lookout Register. From its perch at 9,265 feet, Benchmark has a 100-plus-mile view on a clear day, Zinn said. "This is the kind of job you love or it's the kind of job you hate," she said. "It either suits you or not." Volunteers go through specific training, and above all, they have to be people who can be trusted to relay good information. "We set the standards," she said. "We train to that standard, and we expect that standard." Lookouts are trained to do comprehensive scans every 15 minutes. "Put it this way: If someone changes something in your living room, you know something's off," Zinn said. "When you're used to seeing a particular view, when something is different, you see it. "But after a lightning storm, you're sitting there with the binoculars glued on." They see visitors throughout the season, but it's pretty quiet until hunting season starts, and Zinn cautions that people can distract from the job, and entertaining visitors is at the lookout's discretion. Visitors also should follow typical summer precautions in the mountains and expect afternoon thunderstorms. Contrary to what most people think, the primary job of Zinn and other lookouts is not fire detection. She emphasizes that her primary responsibility is to ensure firefighter safety. "This is an era of catastrophic fires," Zinn said. "We're getting a lot of intense fire behavior. Firefighters can't see the weather coming in, and they can't see overall fire behavior - topography and trees can obscure parts of the fire from their view. I can see that; I'm kind of their eyes." The farthest point that can be seen from Benchmark Lookout is Navajo Mountain, 120 miles away on the Arizona-Utah border near Lake Powell. "You won't see that every day because of the air quality," she said. Zinn has a degree in physics and worked toward a doctorate in atmospheric physics in New Mexico. She said she checks the grounding wires and lightning rods first thing every year when she gets back to the tower to ensure they are intact and undamaged. "It's is very well protected from lightning strikes," she said. The bed sits on a plastic pad, and the chair has glass caps on the legs. Most of the wildfires in this part of the country are lightning-caused, she said. The tower has not been struck, she said, but strikes have hit nearby. Because this area gets "zillions" of lightning strikes, Zinn said, lookouts don't mark the location of each strike. Rather, they note the general geographic location and monitor the area because of the risk of "sleeper fires" caused by strikes that hit then smolder until the conditions are right: the temperature increases, the wind picks up, and a fire starts. |